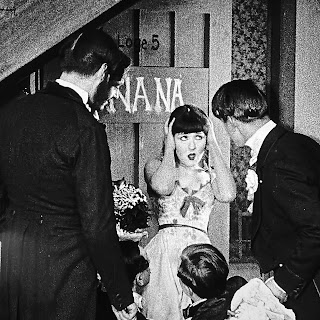

Jane Birkin.

A spirit both material and grounded. Briton-Franco chanteuse, muse, wife of Serge Gainsbourg, auteur of the pop single and the film Je t'aime moi non plus. Outstanding presence in Varda's masterpieces Jane B. par Agnès V. and Kung-Fu Master!. Melody Nelson.Tony Bennett.

Born Anthony Benedetto. Class-act interpreter of the Great American Songbook. A more-than-gifted singer who was bolstered by family and Gaga in his last days, dignified as ever.

Paul Reubens.

I was lucky enough to pay a visit with Pamela Des Barres to Paul (with whom she was close friends) in his dressing room after a preview performance of his Broadway beautiful fantastic comic spectacle The Pee-Wee Herman Show in late 2010 or early 2011. The auteur of Pee-Wee's Playhouse which I watched religiously Saturday mornings as a kid. One brilliant hell of a presence, and a terrific actor. I'd say he was ahead of his time, but he did his part to bring the future of society a couple steps further.

Lelia Goldoni.

Before I got with the Cassavetes crew, I remember mispronouncing her name "Layla," but the actual "Lelia"'s more unique and lilting and beautiful, befitting the young star of Shadows. who 'turns in' a performance for the ages. In many ways, the face in an origin of American independent cinema.

William Friedkin.

I haven't seen half of his films, which I hope to change in 2024. When I was little and becoming obsessed with subliminal images, The Exorcist depicts a scene, almost non-diegetic, in which the (a?) demon's face flashes by in close-up shrouded in pitch black. Imagine trying to pause that on VHS with frame-forwarding. Took a few minutes. True terror came to Hollywood. Not to mention the dinner-party where Regan descends the stairs to confront a soon-to-be-astronaut in attendance and inform him, "You're gonna die up there," before pissing on the rug. Strong stuff. One of the great don't-have-a-shit-to-give raconteurs (presumably flush, and nonetheless the spouse of ex-Paramount head Sherry Lansing). Required viewing for Billy's charm and insouciance is the 2018 Francesco Zippel conversation-documentary Friedkin Uncut.

Gary Young.

The original drummer of Pavement from pre-Slanted and Enchanted up to that masterpiece debut. Another wild lion behind the kit, and before too, like when he'd come out to do a handstand. The subject of the earlier-in-the-year documentary by Jed I. Robinson, Louder Than You Think. Man, the stories I've heard, from Scranton all the way to Ithaca...

Ebrahim Golestan.

At this moment I know very little of the films of the Iranian writer and cinéaste Ebrahim Golestan, which will be rectified in the time ahead. I await seeing Farahani's documentary correspondence-portrait between the late filmmaker and Jean-Luc Godard that was shot in their final months, See You Friday, Robinson.

Samuel Bréan.

A marvelous critic and translator, who actually died in March of this year. I had some correspondence with Samuel years ago around Emmanuel Burdeau's piece on "Godard, la ZAD et le pastiche," and perhaps more recently with his brilliant text on Film Socialisme and its Navajo-English subtitles by Godard. No better example to provide than that essay, originally published in Senses of Cinema in 2011 here.

Bérénice Reynaud.

A critic I admired from the early-2000s around the time of the Movie Mutations drop. I read her articles here and there, but haven't yet read her landmark book Hou Hsiao-hsien's City of Sadness. In a September remembrance issued by CalArts, the following: "This summer, she was planning 'Fourteen Questions for Jean-Luc Godard,' a deep dive into the fimmaker's work before his death last year."

Terence Davies.

In the morass of British cinema, there are contemporary artists who transcend the (especially recent) reputation of a national film industry that repeatedly leaves the good cards on the table — Peter Watkins, Mike Leigh, WEIRDCORE, are examples that come immediately to mind. Terence Davies is another. His

Distant Voices, Still Lives is a supreme masterpiece. I had it out for him for a long spell because in his 2008 essay-doc-film

Of Time and the City he expressed total disinterest in The Beatles. And I thought, I'm not a fan of anyone who's not a fan of The Beatles — since then I've worked through some things.

Keith Baxter.

Prince Hal in Welles' 1966 god-film Falstaff (Chimes at Midnight). A performance that beautifully navigates the transformation of Hal to Henry, just as the power of the performance transforms and complicates and transfixes the viewer with every subsequent viewing.

Dariush Mehrjui.

It shouldn't have come to this — Mehrjui and his wife stabbed to death during a break-in orchestrated by a government that wanted him erased. I first learned of Merhjui from a friend out on the back patio of the Ivy Inn in Princeton, who told me his films were extraordinary — he mentioned The Cow as one of the highlights of his work. The discovery of Iranian cinema, a cinema of martyrs, continues to expand: a determined flourishing, the blood and soil of one of the world's richest film-poetic traditions.

Henri Serre.

The star of Cavalier's Le combat dans l'île (just released on Blu-ray, restored, from Radiance Films) and Truffaut's Jules et Jim. A paragon of the Gallic physiognomy but with a uniquely soulful character...

Burt Young.

...which could be said too of Burt Young. Categorize as, not "They Don't Make Them Like They Used To," which is baloney — more accurate to say "They Don't Hire People Like Him Anymore." Best known as Paulie in the Rocky series, he served as a lynchpin for Robert Aldrich in his strange later fims The Choirboys and Twilight's Last Gleaming, including his final work ...All the Marbles. Was just looking at his biography the other day, and course he owned a restaurant in the Bronx.

Matthew Perry.

Proud of this guy, the funniest Friend, for breaking the chain of addiction. Won't speculate on the ketamine, but his body was nevertheless ravaged. Sounded like, to have him in your acquaintance, he'd be up there with the warmest and funniest of friends.

Michel Ciment.

The first serious book of criticism I read was an English translation (later updated to include Eyes Wide Shut) of Michel Ciment's monolithic Kubrick. Freshman year at school I took Kubrick out of the stacks three separate times to read. Elements of Kubrick I had only sensed at 17 were articulated by Ciment, from "the Kubrick stare" to so on. It's still the best writing on Kubrick I've come across. His ratings in the Cahiers Conseil des Dix were, all told, demented.

Rosalynn Carter.

"Shy and introverted, Rosa can’t stop thinking about that picture on the wall, that uniformed Carter boy with the sweet smile who’s broken the force field and gone far away. He comes home on leave, in the summer of 1945. He’s 20, she’s 17." (Michael Paternini in The New York Times.)

Love is a burden.

Jane (Brakhage) Wodening.

The difference between muse and collaborator, in the face of being the female who takes backseat to the male artist partner and one time husband Stan Brakhage, who precedes later wife Marilyn Brakhage (filmmaker behind the 15-minute 2009 masterpiece, For Stan. — [See also Françoise Gilot.] — Sincerely: It's not subservience, it's love).

From Wodening's Wikipedia page:

"Brakhage and Wodening have both stated that she played a large role in Brakhage's career. In an interview once, Brakhage is quoted as having said, "'By Brakhage' [the Criterion Collection release] should be understood to mean 'by way of Stan and Jane Brakhage,' as it does in all my films since marriage. It is coming to mean: 'by way of Stan and Jane and all the children Brakhage.'" Wodening has reiterated this as well saying: "And so, this point of contention about, was I a partner in Stan's work. Stan said so, over and over again, from the stage. And that's interesting. . . . So, I'll see what I can say, but what I'm speaking from is: I was working on the films." She made films that were 'scrap-books,' and was a prolific author with a deep concern for the environment.

François Musy.

Godard's sound recordist from the 1980s up to 2010's Film Socialisme. Always up to the task, setting new challenges for himself and addressing the audio-wishes of Jean-Luc. "Musy," like "music," appropriate mnemonic. His expertise was put to good use assisting the greatest sound-mind of the cinema artform.

Shane MacGowan.

I grew up in Scranton, Pennsylvania, the 2nd largest Irish hub in the US after Boston, and possibly tied for that number 2 spot by New York City. There were ghosts at the two-story pub The Banshee, who would sidle down the waxed banistered staircase from the upper floor, then either vanish or re-ascend up the steps to the second level. Miners and their families died en masse while boarding at the Banshee building in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Rolling Stone recently wrote of The Pogues' "Fairytale of New York": "When Shane calls her “an old slut on junk,” Kirsty rifles back with a homophobic slur that shocks by today’s standards: “You scumbag, you maggot / You cheap lousy faggot / Happy Christmas your ass / I pray god it’s our last.” (Jon Bon Jovi changed it to “braggart” when he rerecorded it in 2020)." ( — I'm reminded of Mike Love telling an interviewer to look up "braggart, B-R-A-G-G-A-R-T.")

Ken Kelsch.

Abel Ferrara's long-time cinematographer — this will remain (cf. Gary Graver) Ken Kelsch's legacy, or rather, a showcase of his best achievements. Shot the early films; years passed following a falling-out with Abel, and then Kelsch returned to Ferrara's productions at the time of — perfect timing — Bad Lieutenant. No film set could compare to his time in the Vietnam War, which is why his and Abel's films feel like war from start to finish, a maybe-calibrated fight against societal convention and the Cinema of Lies itself. I recommend viewing Mark Rance's 2004, 47-minute documentary A Short Film About the Long Career of Abel Ferrara in order to encounter Kelsch in his prime.

Guy Marchand.

One of those Frenchmen who in the 1960s still showed up in pinstripe suits in the course of carrying out promotional duties. I salute the performer who brought great talent to his participation in Truffaut's Une belle fille comme moi and Pialat's Loulou.

Otar Iosseliani.

A director I discovered in the mid-2000s, with me tuning in to the buzz at the time on the occasion of a complete-works boxset in France that had English subtitles and, as I recall, multiple theatrical screenings in France and wider Europe. There Once Was a Singing Blackbird from 1970 is the one I focused on at the time. I can't wait to finally see the entirety of this iconoclast's body of work.

Tommy Smothers.

"Everybody's talkin' 'bout John and Yoko / Timmy Leary / Rosemary / Tommy Smothers / Bobby Dylan / Tommy Cooper / Derek Taylor / Norman Mailer / Allen Ginsberg / Hare Krishna / Hare, Hare Krishna." – John Lennon

Shecky Greene.

The story goes like this: senior year of school (once again, invoking the quasi-halcyon; stay tuned for the book), my roommate and I late one night called the Vatican, and I asked to speak to the Pope. Actually went through an umbilical line of prelates. I want to believe we'd be connected; my first question was going to be if he ever had the chance to meet Whitley Strieber. I think what happened was, it was going so well, I hung up thinking the rest would ruin it. So the next call we made was to Schecky Greene's manager whereupon we said we were from one of the school's event-planning committees. So we say we'll get him into Kennedy Hall or else The Haunt, but our budget only allows us really to get him work-pay, a take from the house, and travel expenses. As far as lodging went, we told his manager we could set him up nice on our living room couch. Next five minutes are devoted to descriptions of the couch and the apartment. If we'd had access to smartphones in 1999 we could have just texted him photos from the scene. The point is, Shecky Greene could turn dogshit into lemons — unrelenting. Just unrelenting. •

===